A Freethinkers Faith

Novelist Kurt Vonnegut Jr.—of blessed memory—called himself a freethinker. As such, he was not much of a Church goer. When an Episcopal Priest in Manhattan asked if he would lend his skills as a writer to speak about faith; he did. One of the reasons Vonnegut says he wasn’t much of a church goer was because of the frequent quoting of Jesus in the passage, “for the poor with be with you always.”

He said he couldn’t stand the condescension that it brought to poor people by those who are not poor; in the name of religion.

In his meditation on faith Vonnegut doesn’t believe Jesus is giving spiritual advice about treatment of the poor. Jesus is giving his adoration, his attention, to something beautiful; to Mary and the act of love she is lavishing upon Jesus…and the line about the poor; “they will be with you always;” it’s a joke.

“I am enchanted by the Sermon on the Mount. Being merciful, it seems to me, is the only good idea we have received so far. Perhaps we will get another idea that good by and by-and then we will have two good ideas. What might that second good idea be? I don’t know. How could I know? I will make a wild guess that it will come from music somehow. I have often wondered what music is and why we love it so. It may be that music is that second good idea’s being born.

I choose as my text the first eight verses of John twelve, which deal not with Palm Sunday but with the night before-with Palm Sunday Eve, with what we might call ‘Spikenard Saturday.’ I hope that will be close enough to Palm Sunday to leave you more or less satisfied. I asked an Episcopalian priest the other day what I should say to you about Palm Sunday itself. She told me to say that it was a brilliant satire on pomp and circumstance and high honors in this world. So I tell you that. The priest is Carol Anderson, who sold her physical church in order that her spiritual parish might survive. Her parish is All Angels on West Eightieth, just off Broadway. She sold the church but hung on to the parish house. I assume that most, if not all, of the angels are still around. Now as to the verses about Palm Sunday Eve: I choose them because Jesus says something in the eighth verse which many people I have known have taken as proof that Jesus himself occasionally got sick and tired of people who needed mercy all the time. I read from the Revised Standard Bible rather than the King James, because it is easier for me to understand. Also, I will argue afterward that Jesus was only joking, and it is impossible to joke in King James English. The funniest joke in the world, if told in King James English, is doomed to sound like Charlton Heston.

I read: ‘Six days before the Passover, Jesus came to Bethany, where Lazarus was, whom Jesus had raised from the dead. There they made him a supper; Martha served, but Lazarus was one of those at table with him. Mary took a pound of costly ointment of pure nard and anointed the feet of Jesus and wiped his feet with her hair; and the house was filled with the fragrance of the ointment. But Judas Iscariot, one of his disciples (he who was to betray him), said, “Why was this ointment not sold for three hundred denarii and given to the poor?” This he said, not that he cared for the poor but because he was a thief, and as he had the money box he used to take what was put into it. Jesus said, “Let her alone, let her keep it for the day of my burial. The poor you always have with you, but you do not always have me.”

Thus ends the reading, and although I have promised a joke, there is not much of a chuckle in there anywhere. The reading, in fact, ends with at least two quite depressing implications: That Jesus could be a touch self-pitying, and that he was, with his mission to earth about to end, at least momentarily sick and tired of hearing about the poor. The King James version of the last verse, by the way, is almost identical: ‘“For the poor always ye have with you; but you do not always

have me.”’ Whatever it was that Jesus really said to Judas was said in Aramaic, of course - and has come to us through Hebrew and Greek and Latin and archaic English. Maybe he only said something a lot like, ‘The poor you always have with you, but you do not always have me.’ Perhaps a little something has been lost in translation. And let us remember, too, that in translations jokes are commonly the first things to go.

I would like to recapture what has been lost. Why? Because, I, as a Christ-worshipping agnostic, have seen so much un-Christian impatience with the poor encouraged by the quotation, ‘For the poor always ye have with you.’

I am speaking mainly of my youth in Indianapolis, Indiana. No matter where I am and how old I become, I still speak of almost nothing but my youth in Indianapolis, Indiana. Whenever anybody out that way began to worry a lot about the poor people when I was young, some eminently respectable Hoosier, possibly an uncle or an aunt, would say that Jesus himself had given up on doing much about the poor. He or she would paraphrase John twelve, Verse eight: ‘The poor people are hopeless. We’ll always be stuck with them.’

The general company was then free to say that the poor were hopeless because they were so lazy or dumb, that they drank too much and had too many children and kept coal in the bathtub, and so on. Somebody was likely to quote Kin Hubbard, the Hoosier humorist, who said that he knew a man who was so poor that he owned twenty-two dogs. And so on.

If those Hoosiers were still alive, which they are not, I would tell them now that Jesus was only joking, and that he was not even thinking much about the poor.

I would tell them, too, what I don’t have to tell this particular congregation, that jokes can be noble. Laughs are exactly as honorable as tears. Laughter and tears are both responses to frustration and exhaustion, to the futility of thinking and striving anymore. I myself prefer to laugh, since there is less cleaning up to do afterward-and since I can start thinking and striving again that much sooner.

All right: “It is the evening before Palm Sunday. Jesus is frustrated and exhausted. He knows that one of his closest associates will soon betray him for money-and that he is going to be mocked and tortured and killed. He is going to feel all that a mortal feels when he dies in convulsions on the cross. His visit among us is almost over-but life must still go on for just a little while.

It is again suppertime.

How many suppertimes does Jesus have left? Five, I believe. His male companions for this supper are themselves a mockery. One is Judas, who will betray him. The other is Lazarus, who has recently been dead for four days. Lazarus was so dead that he stunk, the Bible says. Lazarus is surely dazed, and not much of a

conversationalist-and not necessarily grateful, either, to be alive again It is a very mixed blessing to be brought back from the dead. If I had read a little farther, we would have learned that there is a crowd outside, crazy to see Lazarus, not Jesus. Lazarus is the man of the hour as far as the crowd is concerned.

Trust a crowd to look at the wrong end of a miracle every time.

There are two sisters of Lazarus there-Martha and Mary. They, at least, are sympathetic and imaginatively helpful. Mary begins to massage and perfume the feet of Jesus Christ with an ointment made from the spikenard plant. Jesus has the bones of a man and is clothed in the flesh of a man-so it must feel awfully nice, what Mary is doing to his feet. Would it be heretical of us to suppose that Jesus closes his eyes?

This is too much for that envious hypocrite Judas who says, trying to be more Catholic than the Pope: ‘Hey-this is very un-Christian. Instead of wasting that stuff on your feet, we should have sold it and given the money to the poor people.’

To which Jesus replies in Aramaic: ‘Judas, don’t worry about it. There will still be plenty of poor people left long after I’m gone.’

This is about what Mark Twain or Abraham Lincoln would have said under similar circumstances.

If Jesus did in fact say that, it is a divine black joke, well suited to the occasion. It says everything about hypocrisy and nothing about the poor. It is a Christian joke, which allows Jesus to remain civil to Judas, but to chide him about his hypocrisy all the same. ‘Judas, don’t worry about it. There will be plenty of poor people left long after I’m gone.’

Shall I regarble it for you? ‘The poor you always have with you, but you do not always have me.’

My own translation does no violence to the words in the Bible. I have changed their order some, not merely to make them into the joke the situation calls for, but to harmonize them, too, with the Sermon on the Mount. The Sermon on the Mount suggests a mercifulness that can never waver or fade.

This has no doubt been a silly sermon. I am sure you do not mind. People don’t come to church for preachments, of course, but to daydream about God. I thank you for your sweetly faked attention.”

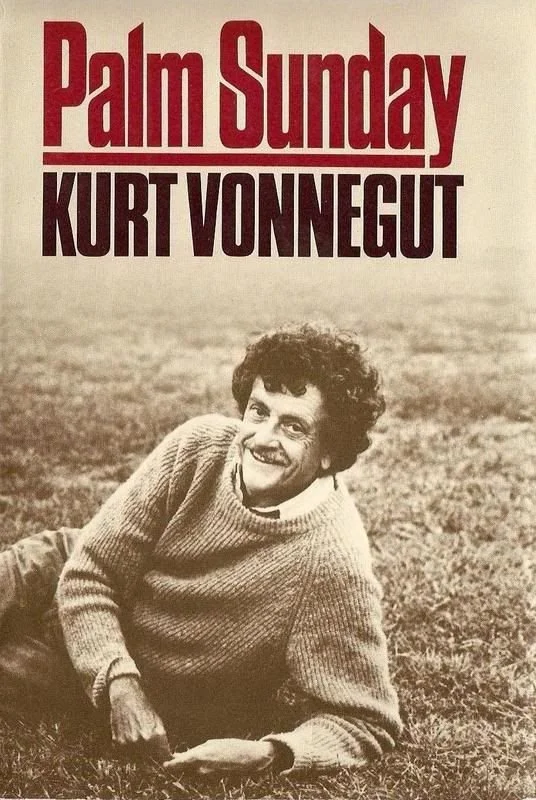

from Kurt Vonnegut's Palm Sunday pages 296-300